Righting a Wrongful Conviction

Film highlights Justin Brooks ’90 and his work to exonerate a young athlete who was wrongfully imprisoned

By Karen Brooks

If you look closely at the whiteboard behind actor Greg Kinnear when he’s briefing interns during an early scene in “Brian Banks,” you can see “follow @justinobrooks” scrawled among the legal jargon. Plugging his Twitter handle is just one of the personal touches criminal defense attorney Justin Brooks ’90 injected into the film.

Kinnear plays Brooks, founder and director of the California Innocence Project (CIP)—a California Western School of Law clinical program that aims to free wrongfully convicted inmates—in the movie. The film’s titular character, Brian Banks, was an All-American high school football player drawing NFL interest when he was falsely accused of raping a classmate. Pressured by his attorney to avoid chancing a life sentence by taking a plea deal, Banks spent more than five years in prison and lost everything: his college scholarship, his reputation, his freedom, and his budding athletic career.

When Banks, played in the film by Aldis Hodge of “Straight Outta Compton” and “Hidden Figures,” first reached out to CIP for help shortly before his release, Brooks hesitated.

“There was no hard evidence establishing a rape, but there was no evidence that would exonerate him, either. Even worse, it’s almost impossible to reverse a plea,” Brooks said. “And we don’t usually represent people who are already out or about to get out of prison. This was just not the kind of case we take on.”

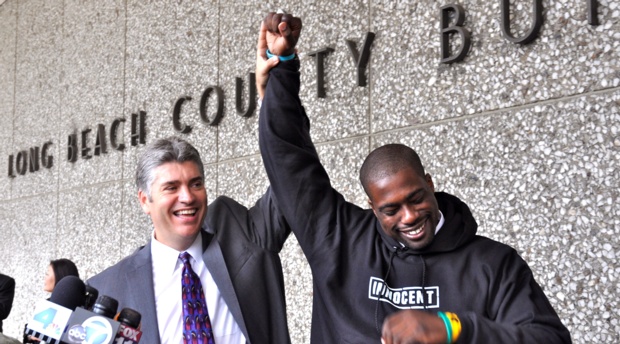

But after Banks reconnected with his accuser and recorded her recanting her story, Brooks reconsidered. “There were a series of hurdles to cross, but on the day of court, the district attorney walked in and said the words I always dream of: ‘We concede.’”

Banks then became the oldest player to join the NFL, signing on as a linebacker with the Atlanta Falcons (Brooks watched his first game from the sidelines). He was soon let go by the team but went on to fulfill another aspiration by working with Brooks to chronicle his experience on film.

“Brian’s story needed to be told, and that story is that sometimes innocent people plead guilty, and we need to understand how and why it happens. This is not a football movie—it’s a movie about the justice system,” said Brooks, who alongside Banks participated in the entire production process, from collaborating with screenwriter Doug Atchison (“Akeelah and the Bee”) to selecting the cast to advising set designers.

Brooks worked particularly closely with Kinnear, who prepared for his role by observing the professor in action at California Western (Brooks laughingly recalled Kinnear’s surprise when his lunch break consisted of a stop at a vending machine). Also starring Sherri Shepherd, Morgan Freeman, and Tiffany Dupont, “Brian Banks” is directed by Tom Shadyac, best known for blockbuster comedies “Ace Ventura,” “Liar, Liar,” “Bruce Almighty,” and “The Nutty Professor.” Shadyac felt compelled to tackle more meaningful subjects after recovering from a serious cycling accident. Before its national release to critical acclaim this past August, the movie premiered at several events, winning a Los Angeles Film Festival Audience Award for Fiction Feature Film and a Humanitas Prize for Independent Feature Film.

For Brooks, the most emotional part of the film follows the final scene, when real photos of him accompanying two decades’ worth of clients as they walk out of prison flash onscreen. Since he founded CIP in 1999, his legal team has freed 30 wrongfully convicted individuals.

“Watching that ending makes it hard for me to speak afterward. Every one of those clients has been on an insane journey that could be made into a movie,” he said, reflecting on a career that “might never have happened” if he hadn’t attended AUWCL. When he enrolled in 1986, Brooks had an undergraduate business degree and intended to pursue a career in corporate law, but his ambitions changed after Professor Ira Robbins took his first-year criminal law class to visit a prison. The trip affected Brooks so deeply that he decided to become a criminal lawyer.

Robbins, who today co-directs AUWCL’s Criminal Justice Practice and Policy Institute, regularly took students to the Lorton Correctional Complex in Fairfax County, Virginia, until it closed in 2001. “I wanted to give them a sense of what it was like to be in a prison—to have them see that many people on the inside are not much different from those on the outside,” he explained. “One reaction was common: After the students were frisked upon entering the facility and then heard several sets of iron gates close behind them, their faces turned ashen and their demeanors became solemn and sober. This helped to put the academic language of criminal law opinions in the casebook in stark perspective.”

Brooks agreed there is no substitute for this kind of experiential lesson. “You can’t teach things like how to do a prison interview in a classroom. The students have to feel it, they have to see it, they have to smell it, they have to do it,” he said. “People in the medical field have realized this for hundreds of years—you don’t make someone a doctor unless they have worked with real patients. It’s the same idea with us, because we’re not training academics. We’re training lawyers.”